As families lose their sources of income due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the global economy plunges into a recession, more households are bound for monetary poverty, with dire consequences for the poorest without access to social protection.

Young people globally are now being negatively affected by the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic and, in some cases, by the mitigation measures that may inadvertently do them more harm than good.

Although this is a universal crisis, for some children and young people, the impact will be lifelong, because the harmful effects will not be distributed equally, as it is expected to be most damaging for children in the poorest neighbourhoods in countries where they are already living under disadvantaged or vulnerable situations.

“I am sad because I may not be able to go back to school now or ever,” says Adwoa Foriwaa (not her real name), a 17-year old form two student of a Senior High School whose destiny and dreams have been shattered after losing both parents to COVID-19. She sobs quietly with her head bowed as she narrates how she received the devastating news from her maternal uncle who brought her home from school.

“My pain is unbearable, but my uncle tells me it will soon go away, and I will be fine, but I don’t think so, and I am very confused and afraid for myself and my two other siblings about this dangerous disease now that Papa and Mama are gone. I cry every day because I can’t focus on my studies, and my friends also shun away from me because my parents died of COVID-19,” she said in an interview with the reporter for ‘Mobilising Media Fighting COVID-19’ project by the Journalists for Human Right.

Foriwaa now lives with her uncle while her other two siblings have been shared among other family members, which she says is causing her much devastation and stress.

For instance, studies by the Ghana Health Service has shown that health care workers, patients with COVID-19, children, women, youth, and the elderly are experiencing post-traumatic stress disorders, anxiety, increased depression, distress, insomnia, suicidal tendencies and a high rate of substance use disorders.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that one in four people will experience a mental health condition in their lifetime, but generally, most people are afraid to even seek help for their mental health status because they think the hospital facilities, might be possible places of getting infected with the due virus.

It says the pandemic has really presented an unprecedented stressor to these vulnerable groups, especially children and adolescents, and the uncertainty of returning to normal life, and prevention of the numerous deaths that are avoidable under usual circumstances, are all likely to increase people’s risk of developing long-term mental health issues.

Nonetheless, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), which is an international human rights treaty, has set out the civil, political, economic, social, health and cultural rights of children, and acknowledges the primary role of parents and the family in the care and protection of young people, and the obligation of the State to help them carry out these duties.

Therefore, under its terms, it clearly requires governments to meet children’s basic needs and help them reach their full potential, and central to which is the acknowledgement that every child has basic fundamental rights.

The Convention, however, includes four articles that are given special emphasis also known as ‘general principles’ and these rights are the bedrock for securing the additional rights in this document, which include the fact that all the rights guaranteed by the UNCRC must be available to all children without discrimination of any kind (Article 2), and that the best interests of the child must be a primary consideration in all actions concerning children (Article 3).

The pandemic is also massively upending education and health services, which have been overstretched, and devastating livelihoods through massive job losses and deaths of loved ones.

It is also well known, for example, that economic insecurity can lead to child marriage as a way to relieve financial pressure on a family, and although there is clear evidence that education is a protective factor against child marriage, school closures such as those triggered by COVID-19 may, in effect, push girls towards marriage since school is no longer an option.

Additionally, the disruption of ‘non-essential’ services including reproductive health services have a direct impact on teenage pregnancy and subsequently on marriage, and all these injustices are silently being tolerated without questioning, because most societies and cultures, including Ghana’s, provides no platforms for listening to the grievances and view of children or young people.

It is with this in mind that the STAR Ghana Foundation decided to fund a media engagement in collaboration with the Ghana Federation of Disability Organizations (GFD) and the Mental Health Society of Ghana (MEHSOG), to highlight the impact of COVID-19 on mental health in Ghana.

The Foundation is also of the view that mental health conditions are likely to begin and assume unimaginable proportions, and would also continue after the pandemic is over, so the subject must be of great concern to all during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, to protect young people especially, from its aggressive grasp.

It, however, classified experiences of the disease, including the breakdown of social support and stigma, as possible causes of short-term mental health problems during this pandemic, while factors such as economic losses can potentially cause long-term issues, as extreme poverty exacerbates mental illness particularly among young people.

They now demand that the subject of mental health and COVID-19 should be included in every school’s curriculum as a test free course, so that students can learn how to take care of their mental health during the pandemic, calling further for the integration of these psychosocial support services into the pandemic response, and sustainably coordinated nationally during and after the pandemic.

Dr Leveana Gyimah, a Psychiatrist at the Pantang Hospital, in a recent article on “Mental Health and COVID-19 in Ghana,” said the field is a unique one, which though relevant in every medical speciality, it is often neglected.

She said it is imperative to encompass mental health as vital to holistic management of the pandemic, saying, “this is not only important for those directly affected by the virus, but the entire population, bearing in mind the specific needs of individuals to avoid long-term complications”.

She said while this may trigger symptoms for those without pre-existing mental illness, such as first responders workplaces and frontline healthcare workers, most of whom are young people, the stress of work, fear of being infected and loss of work colleagues or loved ones, may have a serious psychological toll, and for those who already are living with the condition, this may lead to a relapse or an exacerbation of their condition.

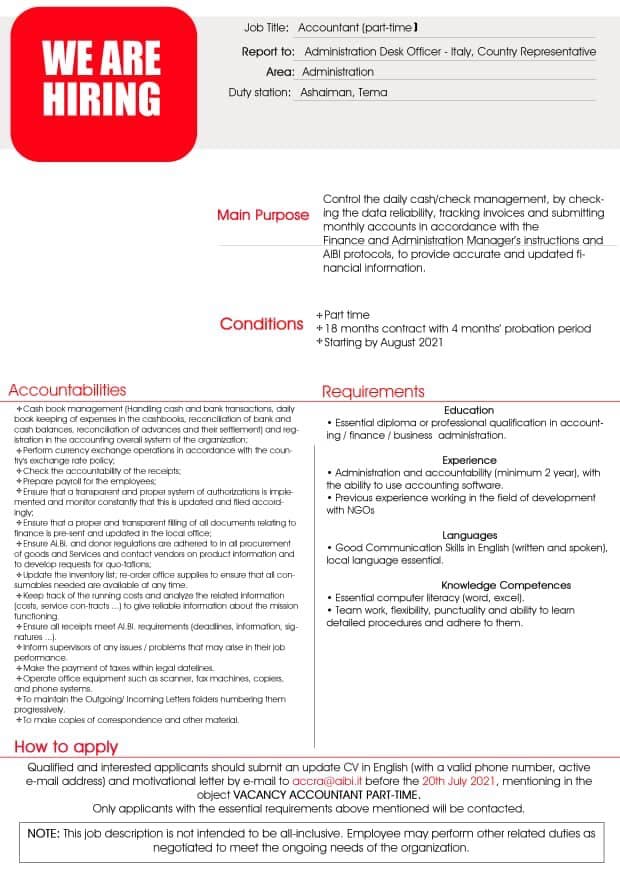

Ms Esenam Drah, the Projects Coordinator for MEHSOG outlined some strategies and gave recommendations to the Government on what needed to be done to curb increasing levels of COVID-19 mental health complications in Ghana.

She said the government needs to do more to scale up mental health services and ensure equity and efficiency. The impact of COVID-19 on mental health in Ghana could be immense, given the weak health care systems.