In Ghana, road repair works—often called “patch patch” by locals—typically occur when an important figure is expected in a particular area. Whether it is the President of the Republic, an upcoming high-profile event like a funeral or Independence Day celebration, or during election periods, road repairs suddenly take priority. However, it is evident that contractors put minimal effort into these works.

Their approach reflects a mindset that these repairs are temporary—just enough to ensure dignitaries can comfortably travel to and from their events. Unfortunately, this is apparent in the poor quality of the work, as weak fundamentals are quickly exposed by the elements. Roads that were hastily patched often deteriorate after a brief period of rain or sun exposure.

In comparison, roads built by foreign contractors in Ghana are notably more durable, highlighting the disparity in quality. A Ghanaian road contractor once expressed his frustration with the challenges they face compared to their foreign counterparts. According to him, funds for road projects often trickle down through several hands before reaching the contractors, by which time the value has significantly depreciated. Meanwhile, prices of materials and fuel increase, and workers demand higher wages.

Most Ghanaian contractors face a dilemma: Should they reject the contract, knowing it will be awarded to someone else? Or should they accept it and attempt to complete the project, despite the nearly impossible conditions?

When I asked why foreign contractors produce better and more durable results despite these challenges, he explained that they usually charge in foreign currencies like the US dollar or Euro and receive substantial portions of the funds upfront. This allows them to work efficiently and meet deadlines. Moreover, many foreign contractors are linked to donors or funding agencies backing the projects, giving them an advantage.

However, it’s worth noting that some Ghanaian contractors, despite receiving similar privileges, have taken advantage of the system, absconding with large sums of money to the detriment of the state.

Our highways, often used by heavy trucks carrying goods across the country, are in terrible condition. Nearly 60% of them are dangerous “death traps” riddled with potholes. Despite claims by successive governments about kilometers of roads constructed, the true test of quality is longevity. Too often, roads start to crumble after just one rainy season.

On some highways, drivers are forced to move at a snail’s pace—covering just 1 kilometer in 3 hours—due to treacherous potholes. Most repairs are quick fixes that barely last a month before the potholes return, often worse than before.

While the government may shoulder some blame, contractors must also take their share of the responsibility. If funding or timing does not meet the agreed-upon terms, contractors should reject the job rather than compromise quality. Money is necessary, but people’s lives are far more important. Many road accidents in Ghana can be attributed to the poor condition of roads.

Drivers often swerve across the road to avoid potholes (as a friend refers to it as dodge one and get two free), leading to frequent vehicle damage and financial losses. Even more frustrating is that the taxes they pay go towards repairing these damaged vehicles, while those responsible for maintaining proper road conditions face no consequences.

Take a drive through farming communities like Afram Plains, and you will see trucks full of foodstuffs abandoned due to impassable roads. This discourages farming and negatively affects the country’s agricultural productivity.

I recall witnessing an incident where a Member of Parliament urged young people in a town to help fill potholes ahead of an election campaign visit by his party’s flag-bearer. However, that night, instead of helping, the youth widened the potholes and created new ones in protest. When the MP confronted them angrily the next day, they explained that an elderly woman from the town had died weeks earlier due to poor road conditions.

To conclude, let me borrow from the words of Jesus in a parable directed at the Pharisees, as recorded in Luke 5:36-38: “No one tears a piece out of a new garment to patch an old one. Otherwise, they will have torn the new garment, and the patch from the new will not match the old. And no one pours new wine into old wineskins. Otherwise, the new wine will burst the skins; the wine will run out, and the wineskins will be ruined. No, new wine must be poured into new wineskins.”

Most of our road repair works are akin to pouring new wine into old wineskins—an exercise in futility.

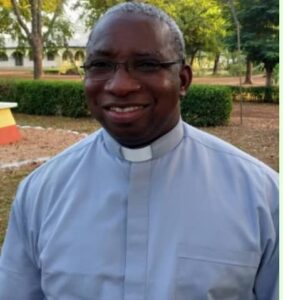

By: Nicholas Nibetol Aazine,

Coordinator for Justice, Peace and Integrity of Creation.

Society of the Divine Word, Ghana-Liberia Province: A Missionary Congregation serving God through Humanity

Email: nicholasbetol@gmail.com